Despite only managing a 10th place finish in La Liga, Marcelo Bielsa’s Athletic Bilbao side of 2011/12 are arguably one of the more memorable teams in Europe from the last decade or so.

Under Bielsa’s guidance, Athletic Club reached the finals of both the Europa League and the Copa del Rey. Sadly they lost both finals 3-0, to Atletico Madrid and Barcelona respectively. However, the style of football they played when they were at their peak level was captivating, trademark Bielsa football, with incredible aggression in all phases of the game.

Much of this analysis is based on the games played by Athletic Club in the Europa League – mainly because these are the only games I was able to find full match footage of, along with a couple of league games, and the Copa del Rey final. Therefore this analysis may be limited in being able to judge their overall league play over the course of the season. However, Athletic Club did put out their strongest team in the Europa League games, and faced a high standard of opposition, so I believe that these games gave a lot of insight into their ability as a team and their tactical profile.

Aggressive man-marking against the ball

In typical Bielsa fashion, Athletic defended with aggressive man-marking across the pitch. It is fairly unusual to see such a defensive system in modern football. Many teams defend in a man-oriented fashion, especially in high pressing, however this is usually within some kind of zonal structure, where players will mark opponents who come into their zone, or at least, they won’t stray too far from their position in order to mark an opponent.

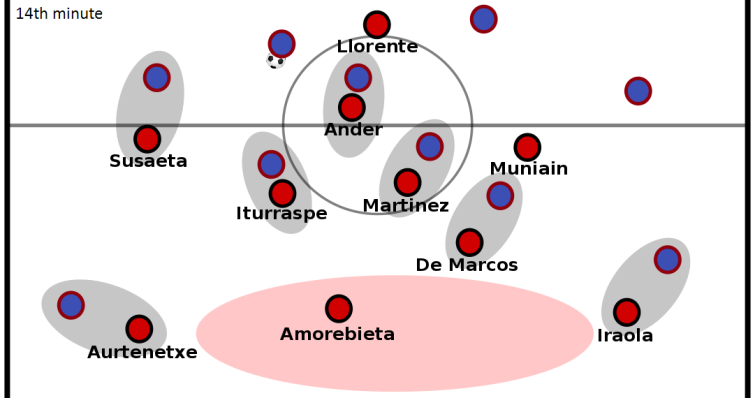

However Athletic operated differently to most teams – players were committed to marking their direct opponent, even if it meant straying far from their nominal position. This is shown in the scene against Barcelona (above), where the central defender Javi Martinez has vacated his position followed Fabregas deep into midfield.

There were some exceptions to the full-pitch man marking – the striker Llorente, naturally didn’t often man mark. His role during the opposition’s buildup was to pressure the ball or otherwise direct the play to one side. Also, the ball-far winger sometimes wouldn’t man-mark the ball-far full-back, in an attempt to maintain some degree of horizontal compactness.

The role of the other central defender as a quasi-sweeper – the spare man who attempts to cover the space left by his teammates, is also seen in this example. The idea of the extra man in defence seems to be another of Bielsa’s preferences. In their Europa League tie against Schalke and their 4-4-2 system, Itturapse dropped back into defence on the occasions when Schalke had possession and both forwards were playing on the last line.

The obvious benefit of the man-marking system for Bilbao’s pressing game was that in a man-marking system, it is in theory possible to pressure every pass and retain access to the ball, as every opponent who receives the ball should be pressured instantly by his marker. This means that in order to progress the ball through the midfield against Bielsa’s side, a high degree of individual pressing resistance was required in order to prevent a loss of possession. Predictably, this was one area in which Barcelona excelled more than most teams who faced Athletic Club, with incredibly press-resistant players such as Xavi, Iniesta and Messi, who are comfortable facing their own goal with the ball.

Defensive weaknesses

Perhaps the most unorthodox aspect to Athletic’s man-marking system was the fact that were willing to use this style of man-marking even when in a low-block. As mentioned previously, many teams operate in a man-oriented way to an extent, such as in high pressing in order to create access, or even sometimes when in a mid-block. However most teams revert to a more zonal system when defending in a low block, in order to focus on protecting the strategically important spaces close to their goal, rather than having their positioning dictated solely by the opponent’s players.

This was where it was easy to see the main weakness of Athletic’s man-marking system, and man-marking in general – the fact that it is inherently reactive: your positioning is dictated by the opponents, and you don’t control space.

This is illustrated in the example from the Europa League tie at home against Manchester United (blue). Athletic’s players are man to man against United’s attackers. As a result, they have no presence in the dangerous space in front of their box, as they lack spatial compactness. Furthermore, the defence is not layered or staggered, giving a very inefficient coverage of space, and making them easier to combine through.

In the end, Rooney, the middle Man Utd player of the three on the edge of the box, peels away into the open space to receive the ground pass, and tries to flick the ball through to one of his teammates on the edge of the box, but doesn’t manage to execute it correctly and the ball runs loose. However the situation shows the weak control of spaces given by man-marking.

The positive for Bielsa’s side was that they didn’t end up defending in a low block as often as most teams, due to the intense pressing which made it difficult for the majority of opponents to play cleanly through the midfield and force Bilbao to retreat into such a low block.

Another way in which Athletic’s defensive system showed weakness was dealing with dribbling – specifically, opposition centre backs carrying the ball forwards in order to provoke pressure – otherwise known in German as ‘andribbeln’.

Andribbeln poses problems for man-marking teams because it forces the defender into a decision – should he pressure the ball carrier in order to stop him making further progress towards goal, or should he stick with the player he is marking in order to prevent him being left open?

If we see man-marking as creating a series of 1v1s (I don’t like conceptualising it as 1v1s, as football is always more complex than that, but we’ll use it here), andribbeln exploits this by adding the ball carrier to the situation, creating a 2v1 against the defender he dribbles towards.

In the scene above, this time from Bilbao’s away game against Manchester United, the United centre back, Chris Smalling in this case, dribbles the ball forward into midfield, and the Bilbao midfielder goes to pressure him. Simply by moving forwards with the ball, the United centre back has now attracted pressure and freed Wayne Rooney in the centre, where before he was marked. Ultimately he chooses to pass wide instead, for Rafael who is running into open space as Bilbao’s left back has been dragged inside.

The lack of spatial compactness in Athletic’s man-marking system was discussed earlier in this piece. It’s effects are also shown in the andribbeln illustration above – namely the lack of defensive connections between Bilbao’s players, caused by the large distances between the player pressuring the ball and his teammates. This makes it easier for opponents to isolate individual defenders and exploit the spaces around them.

These effects are made worse in this particular situation by the fact that the event depicted above comes after a switch of play from the left side, so Athletic were still trying to shift in response to the ball’s new position when Smalling brought the ball out. This only furthers the case for zonal coverage in which the team can remain compact during ball-oriented shifts and ensure strong defensive connections between the players.

Incidentally, Atheltic themselves used the aforementioned tactic of switching from the left side, to the ball-far centre back, to good effect over the two legs against United. In their case it was Javi Martinez who was able to receive the ball and carry it forward – perhaps with better execution than Smalling, who despite creating such andribbeln situations a couple of times in the match, arguably wasn’t able to capitalise on them as much as he could’ve done.

Although I have talked mostly about Athletic’s defensive weaknesses, that is not to say that they were a terrible defensive team. Their defence was often unstable, but a lot can be said for the intensity with which Athletic defended, as mentioned earlier, which in itself prevented most teams from keeping comfortable possession for sustained periods. There were a lot of turnovers in Athletic’s games – both for and against, which is natural when attempting such a high tempo playing style.

Focus on verticality

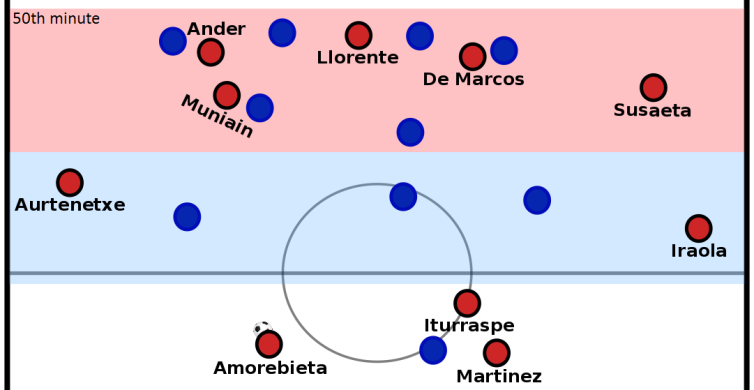

Another aspect of Athletic Bilbao’s game which was to be expected from a Bielsa team was the focus on verticality in attack, with the intention of getting the ball into advanced areas as quickly as possible. This focus was often reflected in their positional structure, as verticality, on a basic level, requires players in advanced areas in order to facilitate forward passing.

A simple and often effective strategy that Bielsa’s side employed was that of long passes to Llorente, with the midfield playing close to him in order to pick up 2nd balls and knockdowns. Having several players in close proximity is also conducive to fast combination play. There are some similarities between Athletic’s use of Llorente and RB Leipzig’s use of Yussuf Poulsen in terms of quickly moving the ball into advanced areas and facilitating combination play. Other times, they were able to find flat passes through the lines. Athletic were fairly good at occupying the spaces between the opposition defence and back 4, and exploiting it through 3rd man runs and layoffs, as well as penetrating with passing combinations such as the ‘up-back-through’.

Of course, there were also issues with such structures. Firstly, the team is rather disconnected – there are a lack of passing options linking the midfield, as illustrated above by Athletic’s lack of presence in the blue highlighted area. However when talking about the structure of a team it is crucial to consider their intentions, and the style of play being aimed for. Therefore if the aim when adopting such a structure is for direct play, then the lack of midfield connections is perhaps less of an immediate problem – although it can make you more predictable and easier to defend.

The more serious problem with Athletic’s structure in these situations was it’s weakness in defensive transition. Often, due to the emphasis on overloading advanced areas, they had an unbalanced shape and weren’t supporting the ball carrier in a way which protected against dangerous counter-attacks.

This also prevented them from having a consistent counterpressing game, at least in the orthodox sense of counterpressing – the defensive transitions were more about recovery runs and backwards pressing, rather than a coordinated counterpress which restricted space and/or options for the ball carrier in a controlled manner.

It should be noted that Athletic weren’t necessarily *bad* at providing support to the ball carrier and connections in midfield – just inconsistent. Sometimes the midfield would be well connected, with Herrera and Muniain for example supporting the ball, other times it wasn’t, as discussed here. This inconsistency was in large part due to the variable positioning of the players when in possession.

General player movements in attack

The player movements in Bilbao’s attack made for some interesting synergies. Muniain was a key player in their attack, moving freely from the left side, able to occupy the left halfspace or drift all the way across the pitch. Him dropping into midfield was also important to Athletic’s buildup play. Furthermore, his blindside movements were incredible, and he used them very effectively and with great dynamism when coming in off of the left wing. On the right, Susaeta’s movements were more linear, but he had the important role of stretching the opponents vertically with frequent runs into depth.

De Marcos and Susaeta interacted well together, with De Marcos making diagonal runs outwards, from the right halfspace towards the wing, often underlapping Susaeta. With their movement patterns and use of depth they were able to open spaces for each other and create complexity for the opposition defenders. Iraola also often complemented Susaeta’s movements, able to both overlap and underlap depending on the situation.

In the centre, Ander Herrera was a key creative force in attack. He was also one of the more active players in attempting to connect the midfield where possible.

Up front, Llorente was important to Bilbao’s direct game, as discussed earlier, with his aerial strength and ability to help attacking combinations by holding the ball up and providing layoffs.

Positional Rotations

One of the aspects which made Athletic’s attack dangerous (and entertaining) was the variable positioning and the rotations from the attackers. The constant movement and position changing not only seeks to create options for the player on the ball, but makes defending more complex for the opposition.

Often Athletic attempted to play quick combinations in fairly small spaces, using rotations to open spaces for each other. The fast movement of both the ball and the players means that two of the defenders’ main reference points upon which they orient themselves are constantly changing, which makes defending extremely challenging, especially for more man-oriented defences.

“I dream of a team where an outsider comes to watch us and can’t understand the roles of the players.” – Marcelo Bielsa

The negative is that such positional freedom, as touched on earlier, is part of the reason for the occasional structural problems in Athletic’s shape, as giving players this freedom inevitably means that they will occasionally create sub-optimal structures for ball circulation and defensive transition.

Right sided overloads

You may have already gathered from this analysis that the right side of Athletic’s attack was the more active one. A key part of their attack was the interactions between Iraola, De Marcos and Susaeta – all rotating between the halfspace and the wing, with the latter two keen to stretch the opposition with runs into depth.

Another way in which they used the right side in the final third was through overloads. Such overloads were naturally afforded to them through the movements discussed – particularly Muniain’s free movement, often drifting all the way to the other wing – as seen in the example (left), which allowed him to use his strengths in small spaces to combine with other players in these overloaded areas.

Within their overloads they incorporated the rotations discussed earlier, constantly moving off-the-ball and looking to open spaces to penetrate through. Often when teams overload one side of the pitch, the underlying intention is to attract the opponent to that side before switching the ball to the other for an isolation situation on the wing (overload to isolate). However this was not usually the result of Bilbao’s overloads, as they often left the ball-far wing unoccupied, as the left back, Aurtenetxe, often stayed narrower, towards the halfspace, or sometimes went into the box looking to arrive at the back post for crosses.

As ever Llorente could also play an important role in these overloads, if necessary supplementing the overload by offering wall-passes with his back to goal to facilitate 3rd man runs. Alternatively he stayed towards the back post in anticipation of crosses, which were a popular route of attack for Athletic. A good thing here was that many of the crosses were from good locations – i.e. close to or inside the box, offering an even greater chance of conversion considering Llorente’s aerial strength.

Similarities to a current team?

In some aspects it could be argued that Bielsa’s Athletic team share similarities with a current team managed by one of Bielsa’s apparent ‘disciples’ – Jorge Sampaoli’s Sevilla. Namely, the focus on verticality, and the disconnect between the back and front players that sometimes arises from this, and the positional freedom in attack with fluid passing combinations.

Conclusion

Overall, I think it is reasonable to label Bielsa’s Athletic Club side as an entertaining yet flawed team. Fortunately, it won’t be too long before we see a Marcelo Bielsa team in action again, with the Argentinian coach set to join Lille in the summer.